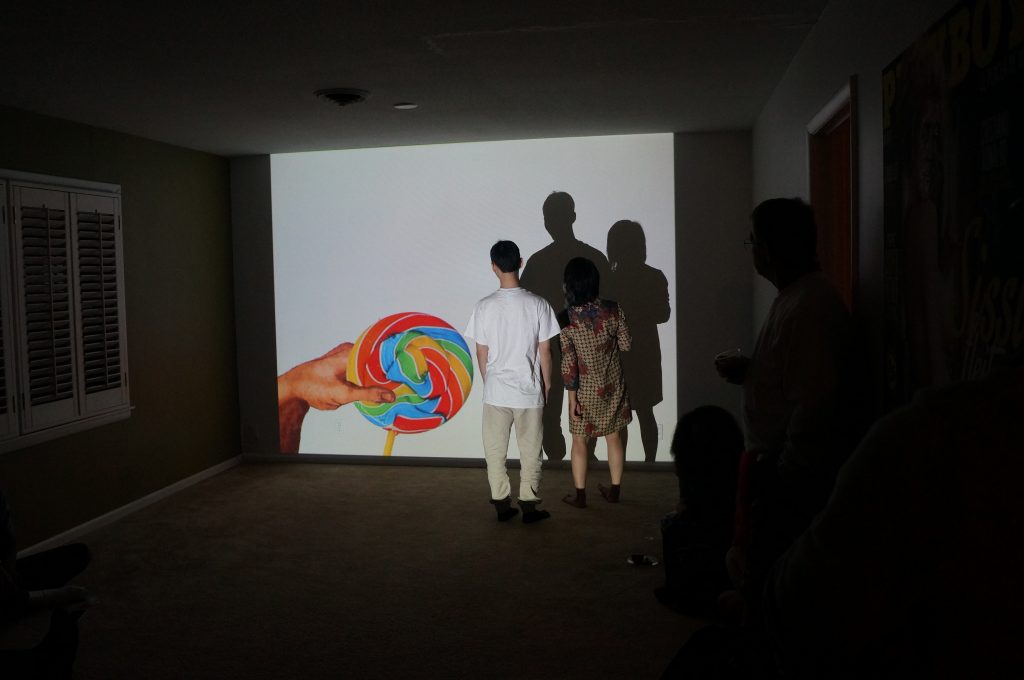

Lollipop showing “The Confusion of Romance” at Expose Art House in Montgomery, AL

Artists are always in search of the next place to show their work and many times turn to alternative art spaces as low-pressure, experimental venues. While the majority of alternative art spaces began in the 1970s and 1980s, the rapid institutionalization and censorship of unconventional spaces in the 1990s caused many of them to die off. In recent years, artists have again been taking the “gallery” into their own hands by independently funding, curating, and exhibiting work in alternative art spaces. These spaces are scattered all over the country, regardless of the city and/or art scene, but are often influenced by the location or setting of the space. They provide artists opportunities to share their work, foster the development of new ideas, and build a network. In many ways, the rise of the alternative art space has been crucial for the preservation of communities and artistic development of both emerging and established artists.

While the development of these spaces mainly took place during the 1970s and 1980s, we can not ignore their historical precedents for which many of these spaces emulated. In the 1950s, Greenwich Village became a hub for diverse artists, and was prominently known for the Tanager, on 90 East 10th Street, and the Hansa, on 70 East 12th Street. These two galleries initiated the cooperative art galleries known as the East 10th Street Galleries in Lower Manhattan (1).Like many of the alternative art spaces of today, the purpose of these galleries was to cultivate the development of artists and their interests in performance, installation, and conceptual art. Therefore, they were small, un-staffed, and dependent on the network of artists. Into the 1960s, the art-centered neighborhood continued to flourish and attracted more artists, but unfortunately the popularity and gentrification of the neighborhood increased the living expenses, pushing many of the artists to find studios and living elsewhere.

Although the East 10th Street Galleries dissipated, there was constant movement towards the development of similar spaces. 112 Greene Street, founded by Jeffrey Lew in 1970, was known as an unstructured, anything-goes, workshop/alternative exhibition space. The space was located in an old factory in the once decrepit neighborhood of SoHo (2). 112 Greene Street offered a place for artists to investigate freely with ideas and materials and became one of the most renowned influences on today’s alternative art spaces. In 1974, the commercialization of SoHo forced the space to accept funding from the National Endowment for the Arts, ultimately sacrificing the integrity of the artist-run space (3),

However, the National Endowment for the Arts had to significantly reduce their funds in the 1990s due to a multitude of controversies. Some speculated that the “graphic” and “provocative” works of Andreas Seranno, Piss Christ, and Robert Mapplethorpe’s retrospective, The Perfect Moment, in 1988-89 pushed the limits too far and were to blame (4). Congress ultimately passed an arts law that restricted funding and ensured that artists who received grants from the NEA would maintain artistic excellence, artistic merit, and take into consideration the standards of decency and values of the American public (5). The lack of funds, rising cost of spaces, and the commercialization of galleries resulted in many spaces relying on fundraising, individual contributions, and private foundations. It is no surprise that organizers of today’s alternative art spaces are turning to more unconventional venues, funding tactics, and social media.

With alternative art spaces on the rise, it seems that the next generation of artists do not want to wait around for gallery representation and/or curatorial positions. Rather, they have decided to create their own opportunities. These spaces serve as a middle-ground between the artist’s studio and academic institutions, mainstream museums and galleries, or local art centers. Artists are able to openly experiment with their work, challenge their artistic practice, and engage their community without the pressures of sales and conventional curatorial expectations. Alternative spaces also provide artists the chance to independently curate, operate residencies, and network. One drastic difference is the omission of application fees. The typical cost of an application is between $30-$60. These costs add up, especially for emerging artists. Alternative spaces still utilize an application process and frequently require the applicant to submit a proposals, curriculum vitae, images, and websites. It is through this process that alternative art spaces are able to establish standards.

The artwork shown within these spaces is often influenced by their location and confines. In the 1950s, ‘60s, and ‘70s the neighborhood often times was the name of the gallery, i.e. East 10th Street Galleries and 112 Greene Street. Names of spaces today are quite similar, as artists are influenced by the location, setting, and/or confines of the space. The location and name also establishes the sort of artwork that is accepted. For instance, Kitchen Space Gallery, run by Traci Fowler and Trevor Schmutz in a Chicago apartment, many times shows work that responds to and/or deals with the conceptual ideas of a kitchen or a home. The best part about Kitchen Space is the fact that Traci and Trevor then live with the artwork, it literally becomes a part of their daily life. The domestic nature of the space was amplified by Alyce Haliday McQueen during her show Sweet Dreams. Alyce, primarily a photographer, was able to experiment with installation art as she covered the counters with crumbling cakes, sticky frosting, smushed cupcakes, vibrant sprinkles, glazed donuts, and pastel kitchenware. To top it off, they kept the whole sticky mess installed for the entire month.

“Sweet Dreams” by Alyce Haliday McQueen at Kitchen Space Gallery in Chicago, IL

Project 1612 (Facebook: Project 1612), the space and short-term residency I co-founded with Alexander Martin and Zach Ott, exists in a garage in Peoria, Illinois. In order to begin this space we utilized the crowd funding site Kickstarter. We raised the entire budget needed to revive the garage, and networked with like-minded artists along the way. While some artists have responded to the garage setting, others have used the city of Peoria to help generate their work. The freedom to experiment with ideas and new methods of making sparks projects that some artists might not have done elsewhere. Erik Peterson, our most recent artist-in-residence, made ink wash drawings with sumi ink and water collected on-site at various locations in the city. The drawings were hung in the space and sticks gathered from those locations were arranged in four separate piles on the floor. During the show Erik invited viewers to select a stick and burn it in a fire behind the garage, he then collected the ashes to make ink, which will be sent to all the participants.

Erik Peterson at Project 1612 in Peoria, IL

Expose Art House (Facebook: Expose Art House) initiated by Chintia Kirana and supported in part by Expose Art Magazine, is based in Montgomery, Alabama. The space also functions as a residency and invites artists to engage with the community through artist talks and workshops. These interactions allow viewers to further understand the artwork, the creative process, and the content of the work. Workshops also draw in other artists, which means there is a greater chance for collaborations. As a member of Backspace Collective, a small artist group in Peoria, Illinois, I know the benefits of collaborating with like-minded artists. One particular collaborative, interactive piece was Select All, a large mixed-media work on canvas that hung from the ceiling during the installation exhibition Guess You Had to be There. Viewers were invited to select a portion from the larger composition and in doing so, they were making compositional choices that artists usually make. Participants then took home their cut pieces and the remaining canvas was then divided among the collective for further use.

While some spaces exist in houses, kitchens, garages, some simply rely on tiny nooks and crannies. Richard Medina’s Box Gallery, for example, is a 6”x6”x6” cardboard box. The idea is simple, manageable, but no less a challenge. TRACTIONARTS, started by Ken Marchionno in Los Angeles, is literally a window facing Traction Avenue where they project videos for the LA Arts District between twilight and midnight. Limitations caused by these spaces require artists to think beyond their normal studio practice, and challenges them to make work specifically for the space.

The online presence of these spaces is just as crucial as the physical space. Fortunately, social media sites like Facebook and Instagram have helped develop followings for many of the spaces, and subsequently serve as a platform for artists and independent curators to meet. Websites, blogs, and online galleries have made it possible for the work of artists outside of major cities to be seen, which means artists can spend more time making, and less time waiting tables in NYC. Furthermore, there has been an increase of artist podcasts, which feeds our need to hear about and understand the lives of artists. These podcasts serve as yet another approach to the alternative art spaces.

There may be an ebb and flow of alternative art spaces, but time and again they prove to be crucial outlets for artists. Emerging and established artists alike have accepted a multitude of responsibilities in this field, from makers, to curators, to artist-in-residency coordinators. And while the commercial gallery system is still relevant, and governmental grants are still needed, artists have an extraordinary need to make and be seen. Alternative art spaces, wherever they may be, will continue to serve and foster the artistic growth of artists.

1 “The 10th Street Galleries.” The Art Story. Accessed April 29, 2016. http://www.theartstory.org/ gallery-10thstreet.htm

2 Kennedy, Randy. “When SoHo Was Young – ‘112 Greene Street: The Early Years,’ ‘70s Art in SoHo.’” The New York Times. July 25, 2012. Accessed April 29, 2016. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/26/ books/112-greene-street-the-early-years-70s-art-in-soho.html?_r=0

3. Walsh, Brienne. “Greener Days: Matta-Clark and Alternative Spaces.” Art In America. January 11, 2011. Accessed April 29, 2016. doi:http://www.artinamericamagazine.com/news-features/news/112-greene- street-zwirner-jessamyn-fiore/.

4 Bauerlein, Mark, and Ellen Grantham. National Endowment for the Arts: A History, 1965-2008. Washington, DC: National Endowment for the Arts, 2009. doi:http://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/nea- history-1965-2008.pdf.

5 Randolph Nea, Courtney. “Content Restrictions and National Endowment for the Arts Funding: An Analysis from the Artist’s Perspective.” William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal. Volume 2, Issue 1, Article 7. Pg. 171. 1993. Access April 29, 2016. http://scholarship.law.wm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi? article=1537&context=wmborj

One thought on “Boxes, Kitchens, & Garages: Alternative Art Spaces”

Pingback: Alternative art Spaces – Uncontained